2.5 Allocating Disk Space

Your first task is to allocate disk space for FreeBSD, and label that space so that sysinstall can prepare it. In order to do this you need to know how FreeBSD expects to find information on the disk.

2.5.1 BIOS Drive Numbering

Before you install and configure FreeBSD on your system, there is an important subject that you should be aware of, especially if you have multiple hard drives.

In a PC running a BIOS-dependent operating system such as MS-DOS or Microsoft Windows, the BIOS is able to abstract the normal disk drive order, and the operating system goes along with the change. This allows the user to boot from a disk drive other than the so-called ``primary master''. This is especially convenient for some users who have found that the simplest and cheapest way to keep a system backup is to buy an identical second hard drive, and perform routine copies of the first drive to the second drive using Ghost or XCOPY . Then, if the first drive fails, or is attacked by a virus, or is scribbled upon by an operating system defect, he can easily recover by instructing the BIOS to logically swap the drives. It is like switching the cables on the drives, but without having to open the case.

More expensive systems with SCSI controllers often include BIOS extensions which allow the SCSI drives to be re-ordered in a similar fashion for up to seven drives.

A user who is accustomed to taking advantage of these features may become surprised when the results with FreeBSD are not as expected. FreeBSD does not use the BIOS, and does not know the ``logical BIOS drive mapping''. This can lead to very perplexing situations, especially when drives are physically identical in geometry, and have also been made as data clones of one another.

When using FreeBSD, always restore the BIOS to natural drive numbering before installing FreeBSD, and then leave it that way. If you need to switch drives around, then do so, but do it the hard way, and open the case and move the jumpers and cables.

2.5.2 Disk Organization

The smallest unit of organization that FreeBSD uses to find files is the filename. Filenames are case-sensitive, which means that readme.txt and README.TXT are two separate files. FreeBSD does not use the extension (.txt) of a file to determine whether the file is program, or a document, or some other form of data.

Files are stored in directories. A directory may contain no files, or it may contain many hundreds of files. A directory can also contain other directories, allowing you to build up a hierarchy of directories within one another. This makes it much easier to organize your data.

Files and directories are referenced by giving the file or directory name, followed by a forward slash, /, followed by any other directory names that are necessary. If you have directory foo, which contains directory bar, which contains the file readme.txt, then the full name, or path to the file is foo/bar/readme.txt.

Directories and files are stored in a filesystem. Each filesystem contains exactly one directory at the very top level, called the root directory for that filesystem. This root directory can then contain other directories.

So far this is probably similar to any other operating system you may have used. There are a few differences; for example, DOS uses \ to separate file and directory names, while MacOS uses :.

FreeBSD does not use drive letters, or other drive names in the path. You would not write c:/foo/bar/readme.txt on FreeBSD.

Instead, one filesystem is designated the root filesystem. The root filesystem's root directory is referred to as /. Every other filesystem is then mounted under the root filesystem. No matter how many disks you have on your FreeBSD system, every directory appears to be part of the same disk.

Suppose you have three filesystems, called A, B, and C. Each filesystem has one root directory, which contains two other directories, called A1, A2 (and likewise B1, B2 and C1, C2).

Call A the root filesystem. If you used the ls command to view the contents of this directory you would see two subdirectories, A1 and A2. The directory tree looks like this:

A filesystem must be mounted on to a directory in another filesystem. So now suppose that you mount filesystem B on to the directory A1. The root directory of B replaces A1, and the directories in B appear accordingly:

Any files that are in the B1 or B2 directories can be reached with the path /A1/B1 or /A1/B2 as necessary. Any files that were in /A1 have been temporarily hidden. They will reappear if B is unmounted from A.

If B had been mounted on A2 then the diagram would look like this:

and the paths would be /A2/B1 and /A2/B2 respectively.

Filesystems can be mounted on top of one another. Continuing the last example, the C filesystem could be mounted on top of the B1 directory in the B filesystem, leading to this arrangement:

Or C could be mounted directly on to the A filesystem, under the A1 directory:

If you are familiar with DOS, this is similar, although not identical, to the join command.

This is not normally something you need to concern yourself with. Typically you create filesystems when installing FreeBSD and decide where to mount them, and then never change them unless you add a new disk.

It is entirely possible to have one large root filesystem, and not need to create any others. There are some drawbacks to this approach, and one advantage.

Benefits of multiple filesystems

-

Different filesystems can have different mount options. For example, with careful planning, the root filesystem can be mounted read-only, making it impossible for you to inadvertently delete or edit a critical file.

-

FreeBSD automatically optimizes the layout of files on a filesystem, depending on how the filesystem is being used. So a filesystem that contains many small files that are written frequently will have a different optimization to one that contains fewer, larger files. By having one big filesystem this optimization breaks down.

-

FreeBSD's filesystems are very robust should you lose power. However, a power loss at a critical point could still damage the structure of the filesystem. By splitting your data over multiple filesystems it is more likely that the system will still come up, making it easier for you to restore from backup as necessary.

Benefit of a single filesystem

-

Filesystems are a fixed size. If you create a filesystem when you install FreeBSD and give it a specific size, you may later discover that you need to make the partition bigger. This is not easily accomplished without backing up, recreating the filesystems with the size, and then restoring.

Important: FreeBSD 4.4 and up have a featured command, the growfs(8), which will makes it possible to increase the size of a filesystem on the fly, removing this limitation.

Filesystems are contained in partitions. This does not have the same meaning as the earlier usage of the term partition in this chapter, because of FreeBSD's Unix heritage. Each partition is identified by a letter, a through to h. Each partition can only contain one filesystem, which means that filesystems are often described by either their typical mount point on the root filesystem, or the letter of the partition they are contained in.

FreeBSD also uses disk space for swap space. Swap space provides FreeBSD with virtual memory. This allows your computer to behave as though it has much more memory than it actually does. When FreeBSD runs out of memory it moves some of the data that is not currently being used to the swap space, and moves it back in (moving something else out) when it needs it.

Some partitions have certain conventions associated with them.

| Partition | Convention |

|---|---|

| a | Normally contains the root filesystem |

| b | Normally contains swap space |

| c | Normally the same size as the enclosing slice. This allows utilities that need to work on the entire slice (for example, a bad block scanner) to work on the c partition. You would not normally create a filesystem on this partition. |

| d | Partition d used to have a special meaning associated with it, although that is now gone. To this day, some tools may operate oddly if told to work on partition d, so sysinstall will not normally create partition d. |

Each partition-that-contains-a-filesystem is stored in what FreeBSD calls a slice. Slice is FreeBSD's term for what were earlier called partitions, and again, this is because of FreeBSD's Unix background. Slices are numbered, starting at 1, through to 4.

Slice numbers follow the device name, prefixed with an s, starting at 1. So ``da0s1'' is the first slice on the first SCSI drive. There can only be four physical slices on a disk, but you can have logical slices inside physical slices of the appropriate type. These extended slices are numbered starting at 5, so ``ad0s5'' is the first extended slice on a disk. These devices are used by file systems that expect to occupy a slice.

Slices, ``dangerously dedicated'' physical drives, and other drives contain partitions, which are represented as letters from a to h. This letter is appended to the device name, so ``da0a'' is the a partition on the first da drive, which is ``dangerously dedicated''. ``ad1s3e'' is the fifth partition in the third slice of the second IDE disk drive.

Finally, each disk on the system is identified. A disk name starts with a code that indicates the type of disk, and then a number, indicating which disk it is. Unlike slices, disk numbering starts at 0. Common codes that you will see are listed in Table 2-2.

When referring to a partition FreeBSD requires that you also name the slice and disk that contains the partition, and when referring to a slice you should also refer to the disk name. Do this by listing the disk name, s, the slice number, and then the partition letter. Examples are shown in Example 2-3.

Example 2-4 shows a conceptual model of the disk layout that should help make things clearer.

In order to install FreeBSD you must first configure the disk slices, then create partitions within the slice you will use for FreeBSD, and then create a filesystem (or swap space) in each partition, and decide where that filesystem will be mounted.

Table 2-2. Disk Device Codes

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ad | ATAPI (IDE) disk |

| da | SCSI direct access disk |

| acd | ATAPI (IDE) CDROM |

| cd | SCSI CDROM |

| fd | Floppy disk |

Example 2-4. Conceptual Model of a Disk

This diagram shows FreeBSD's view of the first IDE disk attached to the system. Assume that the disk is 4 GB in size, and contains two 2 GB slices (DOS partitions). The first slice contains a DOS disk, C:, and the second slice contains a FreeBSD installation. This example FreeBSD installation has three partitions, and a swap partition.

The three partitions will each hold a filesystem. Partition a will be used for the root filesystem, e for the /var directory hierarchy, and f for the /usr directory hierarchy.

2.5.3 Creating Slices using FDisk

Note: No changes you make at this point will be written to the disk. If you think you have made a mistake and want to start again you can use the menus to exit sysinstall and try again. If you get confused and can not see how to exit you can always turn your computer off.

After choosing to begin a standard installation in sysinstall you will be shown this message:

Message

In the next menu, you will need to set up a DOS-style ("fdisk")

partitioning scheme for your hard disk. If you simply wish to devote

all disk space to FreeBSD (overwriting anything else that might be on

the disk(s) selected) then use the (A)ll command to select the default

partitioning scheme followed by a (Q)uit. If you wish to allocate only

free space to FreeBSD, move to a partition marked "unused" and use the

(C)reate command.

[ OK ]

[ Press enter or space ]

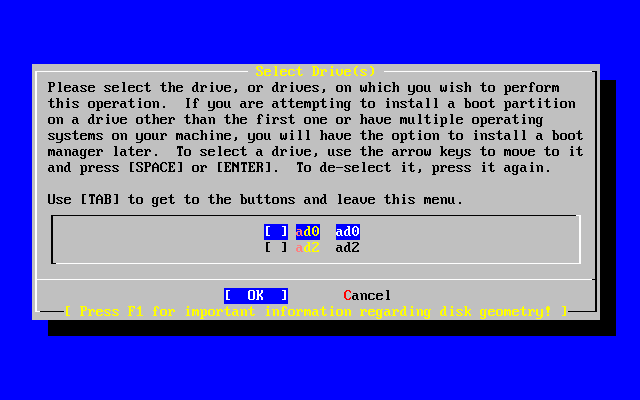

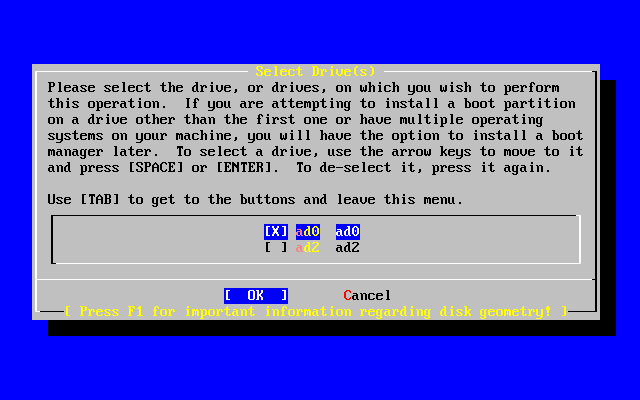

Press Enter as instructed. You will then be shown a list of all the hard drives that the kernel found when it carried out the device probes. Figure 2-16 shows an example from a system with two IDE disks. They have been called ad0 and ad2.

You might be wondering why ad1 is not listed here. Why has it been missed?

Consider what would happen if you had two IDE hard disks, one as the master on the first IDE controller, and one as the master on the second IDE controller. If FreeBSD numbered these as it found them, as ad0 and ad1 then everything would work.

But if you then added a third disk, as the slave device on the first IDE controller, it would now be ad1, and the previous ad1 would become ad2. Because device names (such as ad1s1a) are used to find filesystems, you may suddenly discover that some of your filesystems no longer appear correctly, and you would need to change your FreeBSD configuration.

To work around this, the kernel can be configured to name IDE disks based on where they are, and not the order in which they were found. With this scheme the master disk on the second IDE controller will always be ad2, even if there are no ad0 or ad1 devices.

This configuration is the default for the FreeBSD kernel, which is why this display shows ad0 and ad2. The machine on which this screenshot was taken had IDE disks on both master channels of the IDE controllers, and no disks on the slave channels.

You should select the disk on which you want to install FreeBSD, and then press [ OK ]. FDisk will start, with a display similar to that shown in Figure 2-17.

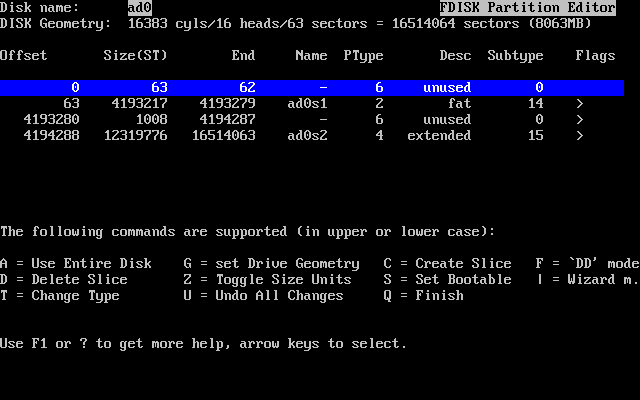

The FDisk display is broken into three sections.

The first section, covering the first two lines of the display, shows details about the currently selected disk, including its FreeBSD name, the disk geometry, and the total size of the disk.

The second section shows the slices that are currently on the disk, where they start and end, how large they are, the name FreeBSD gives them, and their description and sub-type. This example shows two small unused slices, which are artifacts of disk layout schemes on the PC. It also shows one large FAT slice, which almost certainly appears as C: in DOS / Windows, and an extended slice, which may contain other drive letters for DOS / Windows.

The third section shows the commands that are available in FDisk.

What you do now will depend on how you want to slice up your disk.

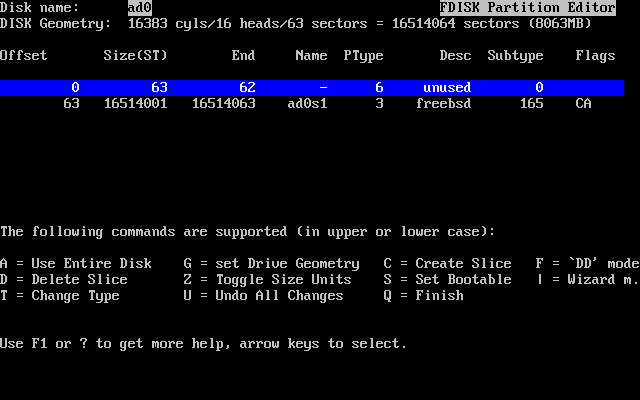

If you want to use FreeBSD for the entire disk (which will delete all the other data on this disk when you confirm that you want sysinstall to continue later in the installation process) then you can press A, which corresponds to the Use Entire Disk option. The existing slices will be removed, and replaced with a small area flagged as unused (again, an artifact of PC disk layout), and then one large slice for FreeBSD. If you do this then you should then select the newly created FreeBSD slice using the arrow keys, and press S to mark the slice as being bootable. The screen will then look very similar to Figure 2-18. Note the A in the Flags column, which indicates that this slice is active, and will be booted from.

If you will be deleting an existing slice to make space for FreeBSD then you should select the slice using the arrow keys, and then press D. You can then press C, and be prompted for size of slice you want to create. Enter the appropriate figure and press Enter.

If you have already made space for FreeBSD (perhaps by using a tool such as Partition Magic) then you can press C to create a new slice. Again, you will be prompted for the size of slice you would like to create.

When finished, press Q. Your changes will be saved in sysinstall, but will not yet be written to disk.

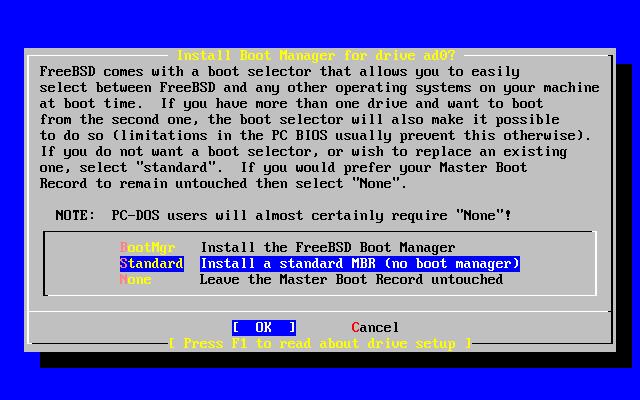

2.5.4 Install a Boot Manager

You now have the option to install a boot manager. In general, you should choose to install the FreeBSD boot manager if:

-

You have more than one drive, and have installed FreeBSD onto a drive other than the first one.

-

You have installed FreeBSD alongside another operating system on the same disk, and you want to choose whether to start FreeBSD or the other operating system when you start the computer.

Make your choice and press Enter.

The help screen, reached by pressing F1, discusses the problems that can be encountered when trying to share the hard disk between operating systems.

2.5.5 Creating Slices on Another Drive

If there is more than one drive, it will return to the Select Drives screen after the boot manager selection. If you wish to install FreeBSD on to more than one disk, then you can select another disk here and repeat the slice process using FDisk.

The Tab key toggles between the last drive selected, [ OK ], and [ Cancel ].

Press the Tab once to toggle to the [ OK ], then press Enter to continue with the installation.

2.5.6 Creating Partitions using Disklabel

You must now create some partitions inside each slice that you have just created. Remember that each partition is lettered, from a through to h, and that partitions b, c, and d have conventional meanings that you should adhere to.

Certain applications can benefit from particular partition schemes, especially if you are laying out partitions across more than one disk. However, for this, your first FreeBSD installation, you do not need to give too much thought to how you partition the disk. It is more important that you install FreeBSD and start learning how to use it. You can always re-install FreeBSD to change your partition scheme when you are more familiar with the operating system.

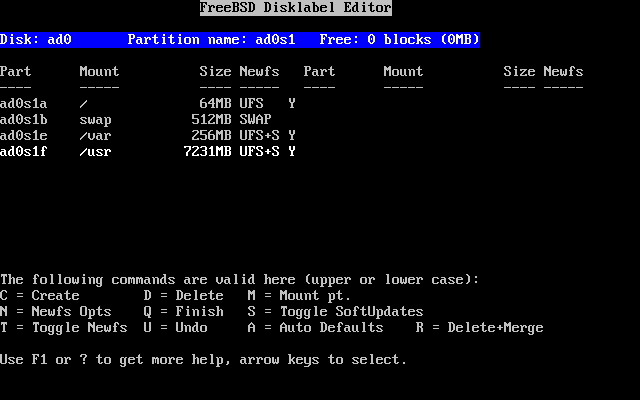

This scheme features four partitions--one for swap space, and three for filesystems.

Table 2-3. Partition Layout for First Disk

| Partition | Filesystem | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | / | 100 MB | This is the root filesystem. Every other filesystem will be mounted somewhere under this one. 100 MB is a reasonable size for this filesystem. You will not be storing too much data on it, as a regular FreeBSD install will put about 40 MB of data here. The remaining space is for temporary data, and also leaves expansion space if future versions of FreeBSD need more space in /. |

| b | N/A | 2-3 x RAM |

The system's swap space is kept on this partition. Choosing the right amount of swap space can be a bit of an art. A good rule of thumb is that your swap space should be two or three times as much as the available physical memory (RAM). You should also have at least 64 MB of swap, so if you have less than 32 MB of RAM in your computer then set the swap amount to 64 MB. If you have more than one disk then you can put swap space on each disk. FreeBSD will then use each disk for swap, which effectively speeds up the act of swapping. In this case, calculate the total amount of swap you need (e.g., 128 MB), and then divide this by the number of disks you have (e.g., two disks) to give the amount of swap you should put on each disk, in this example, 64 MB of swap per disk. |

| e | /var | 50 MB | The /var directory contains variable length files; log files, and other administrative files. Many of these files are read-from or written-to extensively during FreeBSD's day-to-day running. Putting these files on another filesystem allows FreeBSD to optimise the access of these files without affecting other files in other directories that do not have the same access pattern. |

| f | /usr | Rest of disk | All your other files will typically be stored in /usr, and its subdirectories. |

If you will be installing FreeBSD on to more than one disk then you must also create partitions in the other slices that you configured. The easiest way to do this is to create two partitions on each disk, one for the swap space, and one for a filesystem.

Table 2-4. Partition Layout for Subsequent Disks

| Partition | Filesystem | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| b | N/A | See description | As already discussed, you can split swap space across each disk. Even though the a partition is free, convention dictates that swap space stays on the b partition. |

| e | /diskn | Rest of disk | The rest of the disk is taken up with one big partition. This could easily be put on the a partition, instead of the e partition. However, convention says that the a partition on a slice is reserved for the filesystem that will be the root (/) filesystem. You do not have to follow this convention, but sysinstall does, so following it yourself makes the installation slightly cleaner. You can choose to mount this filesystem anywhere; this example suggests that you mount them as directories /diskn, where n is a number that changes for each disk. But you can use another scheme if you prefer. |

Having chosen your partition layout you can now create it using sysinstall. You will see this message:

Message

Now, you need to create BSD partitions inside of the fdisk

partition(s) just created. If you have a reasonable amount of disk

space (200MB or more) and don't have any special requirements, simply

use the (A)uto command to allocate space automatically. If you have

more specific needs or just don't care for the layout chosen by

(A)uto, press F1 for more information on manual layout.

[ OK ]

[ Press enter or space ]

Press Enter to start the FreeBSD partition editor, called Disklabel.

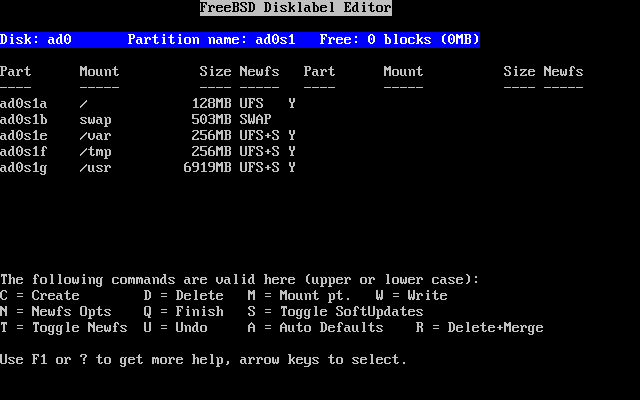

Figure 2-21 shows the display when you first start Disklabel. The display is divided in to three sections.

The first few lines show the name of the disk you are currently working on, and the slice that contains the partitions you are creating (at this point Disklabel calls this the Partition name rather than slice name). This display also shows the amount of free space within the slice; that is, space that was set aside in the slice, but that has not yet been assigned to a partition.

The middle of the display shows the partitions that have been created, the name of the filesystem that each partition contains, their size, and some options pertaining to the creation of the filesystem.

The bottom third of the screen shows the keystrokes that are valid in Disklabel.

Disklabel can automatically create partitions for you and assign them default sizes. Try this now, by Pressing A. You will see a display similar to that shown in Figure 2-22. Depending on the size of the disk you are using the defaults may or may not be appropriate. This does not matter, as you do not have to accept the defaults.

Note: Beginning with FreeBSD 4.5, the default partitioning assigns the /tmp directory its own partition instead of being part of the / partition. This helps avoid filling the / partition with temporary files.

To delete the suggested partitions, and replace them with your own, use the arrow keys to select the first partition, and press D to delete it. Repeat this to delete all the suggested partitions.

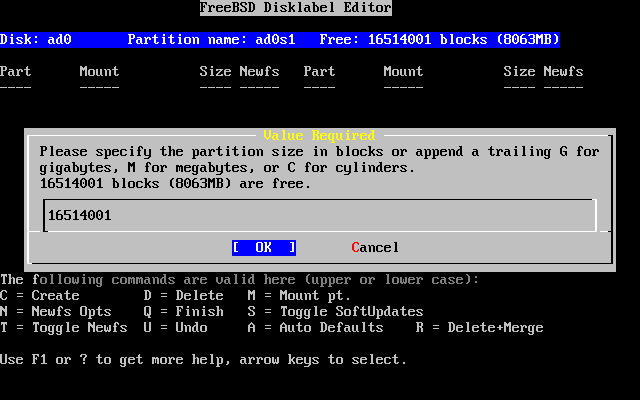

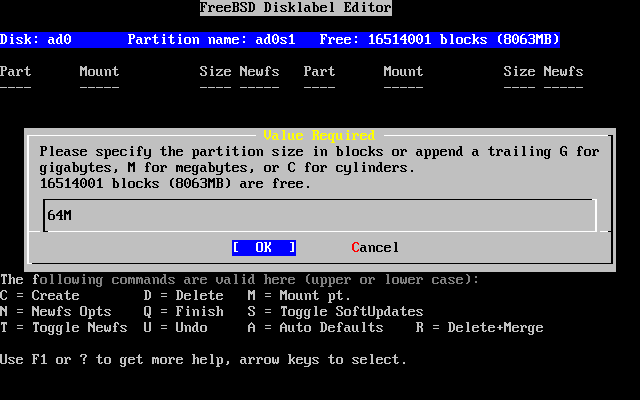

To create the first partition (a, mounted as /), make sure the disk information at the top of the screen is selected, and press C. A dialog box will appear prompting you for the size of the new partition (as shown in Figure 2-23). You can enter the size as the number of disk blocks you want to use, or, more usefully, as a number followed by either M for megabytes, G for gigabytes, or C for cylinders.

The default size shown will create a partition that takes up the rest of the slice. If you are using the partition sizes described earlier, then delete the existing figure using Backspace, and then type in 64M, as shown in Figure 2-24. Then press [ OK ].

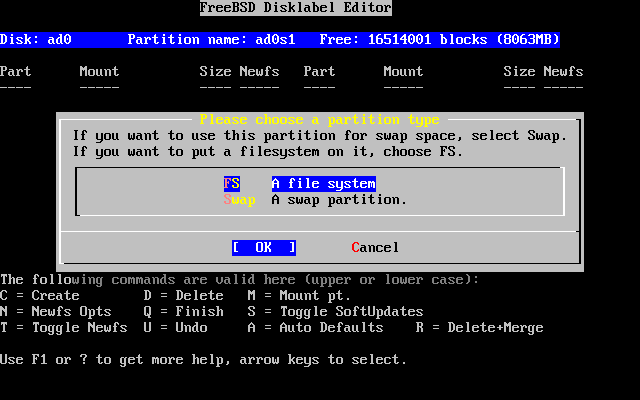

Having chosen the partition's size you will then asked whether this partition will contain a filesystem or swap space. The dialog box is shown in Figure 2-25. This first partition will contain a filesystem, so check that FS is selected and then press Enter.

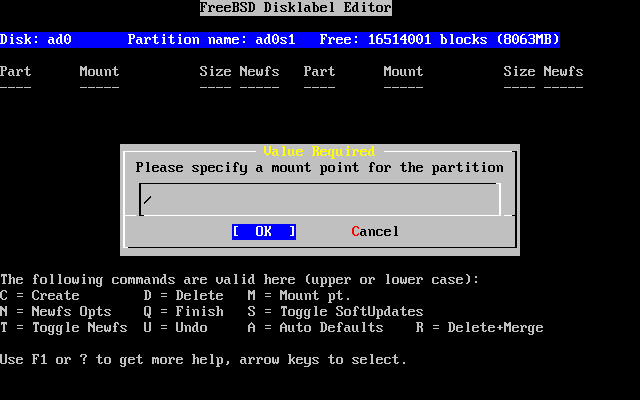

Finally, because you are creating a filesystem, you must tell Disklabel where the filesystem is to be mounted. The dialog box is shown in Figure 2-26. The root filesystem's mount point is /, so type /, and then press Enter.

The display will then update to show you the newly created partition. You should repeat this procedure for the other partitions. When you create the swap partition you will not be prompted for the filesystem mount point, as swap partitions are never mounted. When you create the final partition, /usr, you can leave the suggested size as is, to use the rest of the slice.

Your final FreeBSD DiskLabel Editor screen will appear similar to Figure 2-27, although your values chosen may be different. Press Q to finish.